In the classroom a fascinated silence fell. Lila half smiled, almost a grimace, and flung herself sideways, against her deskmate, who was visibly irritated. Then she read in a sullen tone: “Sun.” […] According to Rino, Lila’s older brother, she had learned to read at the age of around three by looking at the letters and pictures in his primer. She would sit next to him in the kitchen while he was doing his homework, and she learned more than he did.*

(Chapters 6-7)

This extract from L’amiga geniale by Elena Ferrante recounts the day Lila, the main protagonist, surprises her classmates and professor by revealing she had learnt to read before having been taught. This premature achievement of hers was not an isolated incident but rather a foreshadowing of her future exceptional capabilities in all matters academic. Indeed, the scientific research published to date confirms what is laid out in this novel: that young children’s basic skills are strong predictors of their prospective academic achievement. Indeed, numeracy and literacy skills – which make up the set of these basic skills – can greatly help – or hinder when insufficient – the acquisition of further skills later on. According to Juel (1988), notably, children with reading difficulties in the first year of primary school have 88% of chances to continue experiencing these difficulties in the fourth year. It is therefore important to ensure children’s acquisition of these skills early in their education.

But evidence also suggests that the acquisition of such basic numeracy and literacy skills starts before early childhood education even starts. Juel’s very longitudinal study starts with the identification of poor readers from others as early as the first grade. And to quote Ferrante’s novel again, Lila had gotten familiar with literacy by merely observing her brother and his books outside of a classroom setting – so much so that she had actually figured out how to read by herself. Now, while it cannot be expected that children learn how to read before entering primary school, it is still paramount that they be exposed to books and reading as she was, before their first day in a classroom. Such exposure, and the familiarity with letters and pages that goes with it, has been designated as “print awareness” or “print knowledge”.

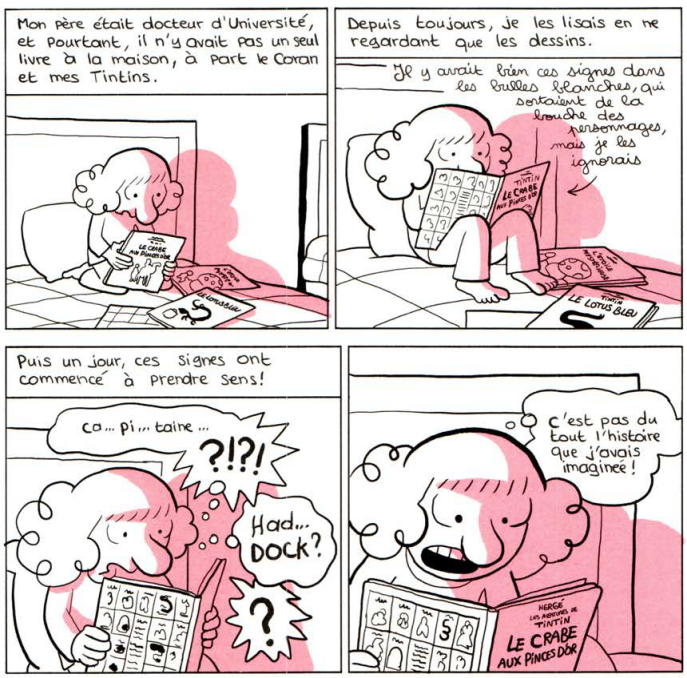

My dad was a university professor and yet, he didn’t have a single book at home except for the Coran and my Tintin volumes.

I had been reading them by watching the illustrations since forever. I did see the white bubbles emerging from the characters’ mouths but I would just ignore them.

Until one day these signs started making sense. “Ca…p…tain… Had…DOCK?”

This is not at all the story I had been imagining!

Indeed, even if print knowledge doesn’t directly translate to reading ability, the literature suggests that it does play a significant role in young children’s later development of reading – or literacy – skills as well as, interestingly, numeracy skills. According to Purpura (2015), this can be explained by the fact that print knowledge helps familiarise children with the idea of an “underlying code of applying names and meanings to symbols” which it shares with both literacy of course, but also numeracy. (Purpura 2015 : 212) That is, once children understand that letters, pictures and symbols printed on a page can represent words and numbers and in this way, can mean things and quantities in the physical world (a principle of print knowledge), they are better equipped to manipulate such written symbols in the framework of their literary and numerical instruction.

Moreover, print knowledge doesn’t stop there, but also familiarises children with books themselves as objects: the handling of them, the awareness that they are to be read from left to right on the page and between pages and from bottom to top line by line within a page, and the critical thinking involved behind choosing them (which in turn involves reading the title, the back cover summary, skimming through the table of contents, navigating through the pages, etc.). Such familiarity with the primary tools of any formal instruction can only be conducive to a better academic performance down the line (Purpura 2015 : 200), but one must note that it will soon also raise the question of how print knowledge acquisition will evolve as the shift to digital books progresses.

In conclusion, the acquisition of children’s basic skills – which are important in their future academic achievement – does not start on their first day of school, but before. One factor that can aid their acquisition of both literacy and numeracy is as simple as their familiarity with printed material and the print knowledge that goes with it. On the one hand, this comes off as good news as it suggests parents can somewhat effortlessly improve their children’s academic potential through informal means prior to their introduction to school. On the other hand, it does sound concerning from a societal perspective as it is usually children in lower social classes who are the least exposed to printed material. This leaves room only for particularly gifted children such as Lila (L’amica geniale), or particularly stimulated ones such as Riad (L’arabe du futur) to benefit from a seamless acquisition of basic skills in literacy and numeracy.

*Original extract: Nell’aula cadde un silenzio incuriosito. Lila fece un mezzo sorrisetto, quasi una smorfia, e si gettò di lato, tutta addosso alla sua compagna di banco, che diede molti segni di fastidio. Poi lesse con tono imbronciato: «Sole». […] Secondo Rino, il fratello più grande di Lila, la bambina aveva imparato a leggere intorno ai tre anni guardando le lettere e le figure del suo sillabario. Gli si metteva seduta accanto in cucina mentre faceva i compiti, e apprendeva più di quanto riuscisse ad apprendere lui.

Bibliography:

Ferrante, Elena. My brilliant friend. Europa Editions UK, 2012.

Juel, Connie. “Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades.” Journal of educational Psychology 80.4 (1988): 437.

Purpura, David J., and Amy R. Napoli. “Early numeracy and literacy: Untangling the relation between specific components.” Mathematical Thinking and Learning 17.2-3 (2015): 197-218.

Sattouf, Riad. L’Arabe du futur (Tome 2): Une jeunesse au Moyen-Orient (1984-1985). Allary éditions, 2015.